The Social Connection

/Earlier this month, we opened our season at the home of Nirav Kamdar, a young anaesthesiology professor at UCLA. To say that his heart is in the right place when it comes to connecting with others would be an understatement. Nirav is an exceptionally gracious host, and an enthusiastic supporter of live music. (Malcolm Gladwell might describe him as a "maven.")

Something special happens when you play in someone's home. The atmosphere is alive with a spirit of hospitality, conviviality, and sharing. The tone of engagement with other people changes. Comfort replaces stiffness. Conversation -- the truest kind of "audience engagement" -- is organic.

All this has a friendly and equalizing effect. Even now, it doesn't feel right to refer to those who came out that night as "the audience." The 60 guests who attended consisted of a few of our loyal patrons, plus friends and colleagues of Nirav's. Their level of familiarity with classical music varied widely. Regardless, their enjoyment of the evening was as consistent as it was palpable.

Many of those who came belong to classical music's most elusive demographic: millenials. Hearing how inspired they felt reminded me of something that had been bugging me for months.

I declined to mention in my last post that our rebranding process had thrown a big, fat pebble in my shoe. The pebble in question:

Why is classical music such a f*&%ing tough sell?

The 'product' itself is profoundly meaningful. It has the potential to appeal to many more, and certainly more diverse, people than it has come to attract.

So why doesn't it? How does an art form so interesting and enriching come to generate so little FOMO? Why should it warrant an entire NPR podcast episode called "How to actually enjoy yourself at the symphony?"

These questions had been on my mind for months. Nirav's house concert provided a perfect, informal focus group. Over and over, I heard people express how much they enjoyed the music and the environment. They felt comfortable, inspired, and most importantly, like they belonged. The implication here was that that feeling is absent the rest of the time.

An intrinsic catch-22

Of all the arts, music helps us connect most readily to something beyond, and to each other. I like to imagine that music originated out of our human need to consecrate special events. To this day, music is universally integral to weddings, funerals, and religious rites. In a more quotidian sense, I also like to imagine cavemen making music together to pass the time.

There's something else all these events have in common: sharing intimately with other people.

Sitting politely in a giant hall among anonymous hordes -- most of whom are elderly? With rules about when, and how, to applaud? Enjoyment and understanding implicitly contingent upon the presumption of a certain degree of knowledge? Donor recognition reminding you of social and economic circles to which you don't belong?

You could call sitting politely customary; the giant hall an instrument of acoustic perfection; and ageism a who-cares truth. You could call rules about when and how to applaud a means to a more experientially reflective end. You could call the presumption of knowledge a legitimate prerequisite. And most classical music performances wouldn't exist at all without donor recognition.

This setting is my world, and has been for most of my life. I move comfortably in it.

But not everybody does. More and more, I feel that the culture around classical music poses intrinsic challenges. What it's has come to project is, at best, unmatched depth. At worst, that same depth translates to inaccessibility. Like it or not, classical music has become equated with distancing, lofty grandiosity. While the music itself is fantastically unrestrained, you can't say the same for the culture around it.

That's where I think classical music's intrinsic Catch 22 lies. Why it is such a f*&%ing tough sell.

Elitism's bad rap

elitist

adjective

1. (of a person or class of persons) considered superior by others or by themselves, as in intellect, talent, power, wealth, or position in society

2. catering to or associated with an elitist class, its ideologies, or its institutions

Classical music's identity and appeal rest on its depth. Likewise, its value rests on historic heights of intellect and talent; of beauty and genius.

Well-meaning musicians and presenters (ahem) believe that this art has universally enobling potential. Let's not forget Salastina's mission statement: "enriching hearts and minds through chamber music."

Elitist? Guilty as charged.

Another salient trope around classical music is its association with preternatural evil. I love how Slate Magazine puts it in the preface to this video clip, "Villains Love Classical Music:"

Perhaps there's no accounting for their killer taste, except that screenwriters seem to use classical again and again to signify that these baddies are frightfully intelligent, have a flair for the dramatic, and are too sophisticated to be trusted.

Fun fact: I was an extra in the penultimate clip.

Indeed: turning all these grandiose, dramatic, elitist undertones into an open invitation is no easy task.

Exposure isn't enough

Orchestras have long subscribed to a seductive myth: that exposing people to music will hook them. Get a newbie in the hall, and they'll be transformed. They'll crave more. The music is that powerful.

Sheer exposure can achieve the desired result with a certain kind of person. But for most, it's ineffective.

Why is that? Yes, new listeners are being exposed to some of the greatest art ever created. But they are also being exposed to a culture that feels, at times, stifling.

The visual art world, on the other hand, is successfully leveraging social media to attract younger crowds. This great Atlantic article looks at how museums are adapting to the Instagram era by mounting large-scale exhibitions designed to appeal to younger viewers.

"These exhibitions are often more akin to stadium concerts than museum shows, starting with the lines that precede them. They overwhelm the senses, offer a communal experience as opposed to a personal one, and provide fantastic photo opportunities while making friends jealous.

Exhibitions like “Wonder”—which drew more visitors in six weeks than the Renwick had previously hosted in one year—are on the rise, as institutions seek to capitalize on the promotional power of social media. Increasingly, shows feature big, bold, spectacular works that translate into showy Instagram pictures or Snap stories, allowing art to wow people who might otherwise rarely set foot inside museums."

Part of the Renwick's much-instagrammed "Wonder" exhibit: Plexus 10 by Gabriel Dawe. say what you want about it -- it's delightfully whimsical.

The new Broad Museum is right across the street from Colburn, where I teach chamber music on Saturdays. Week after week, I've marveled at the long lines. Although I questioned its aesthetic appeal while it was under construction, the honeycomb backdrop of the facade is compelling, and already iconic. It provides the perfect Instagram-worthy backdrop for selfies. I've borne witness to dozens of them. And I've seen, as you likely have, many pictures of the art within on social media.

The art now on display in many museums is changing with the times. That fact is not without controversy; critics bemoan the "superficiality" of the art presented.

"The trend toward accessibility has its critics, who wonder whether the sensationalist works being exhibited are worthy of all the attention, not to mention whether the smartphone photography is getting in the way of people looking and thinking about the art in front of them.

... there’s a downside to all this sharing. The old processes of “intellectual legitimation” that once defined experiencing art are traded ... for “simple visibility.” In other words, there’s a lack of quality control. Large-scale art installations, especially those in festival settings, are able to bypass the old structures that determined good and bad art by capitalizing on collective attention."

Accessibility versus the intellectual elite, as it pertains to fine art... hmm. Remind you of anything?

"But while the art establishment may look down on larger-than-life art because of its lack of subtlety, the spectacular, emotional nature of ... exhibitions like “Wonder” ultimately makes them more accessible to viewers who may feel excluded from the conceptually aloof art found in many institutions."

It's easy to imagine the average layperson finding a presumption or expectation of knowledge off-putting. I've come across well-meaning evangelizers who insist that artistic or musical knowledge is a gateway to enjoyment. (I subscribe to a bit of that myself; though I think the critical factor is how and what you share.) I've also come across less-generous rationalists who correlate enjoyment of 'sophisticated' art with intelligence.

Neither scenario is particularly inviting. Nor does either inspire curiosity the way many presenters and performers hope (and expect) it to.

Although my husband and I enjoy wine very much, it's fair to say we are ignoramuses on the subject. Several of our friends and family are far more educated than we are. My dad and my sister-in-law are practically experts. If we drank the same glass of wine, would they appreciate or dislike it more than me? Would they be more right in their opinions? Probably. But would that invalidate or diminish my enjoyment of the wine? (It's probably worth noting the obvious here: that even wine culture has a reputation for off-putting snobbery.)

A few years ago, Phil and I took an afternoon class on food and wine pairings. It was a guided experience in which the sommelier pointed things out in each pairing. It was extremely fun. And it did change how we taste and experience wine, and wine pairings with food, a little bit. I'd say we enjoy it a bit more now having learned and discovered what we did. And we feel a bit more confident in our tastes and opinions -- though we still readily concede our newbie-ness.

Not that far off.

To me, enjoyment of music is no different.

"Nicholas R. Bell, the curator of “Wonder,” disagrees with the idea that there’s a “proper” way to experience art, or that large-scale installations are somehow inferior. “Have we not clamored for spectacle for thousands of years?” he says. “People like large things that overpower them in some way. I think it’s part of human nature.”

... Regardless of critics’ reservations, large-scale art’s growing presence on social media doesn’t necessarily deprive it of gravitas or make it less worthy of attention. Engaging people with art in any way possible is, for many museums, the first step in persuading them of its deeper value. And taking photos of works, however performative it may be, is a way for people to show off what’s important to them. “Different people will achieve their most meaningful experience in a museum in various ways,” Bell says. “And I don’t think we should be the arbiter of that.”

I find Mr. Bell's candid acceptance of human nature, as it pertains to interacting with art, refreshing. "Showing off what's important to them" is a stronger, and perhaps less generous, way of expressing two perfectly human desires:

- to share their values with others; and

- to let their identity be known to others.

Throughout our conversations with Nirav, the topic of developing friendship came up repeatedly. He is the newest member of our advisory board.

Friends through music, new and old: Brian Lauritzen, Nirav Kamdar, Steven Vanhauwaert, yours truly, and Kevin.

FOMO is inherently social

In August, Kevin, Meredith, our friend Trevor, and I performed at a trendy Highland Park venue packed with young people. Kensington Presents produced the event. We were opening for the Raising Sand Tribute Band.

Our favorite audience shot from that night.

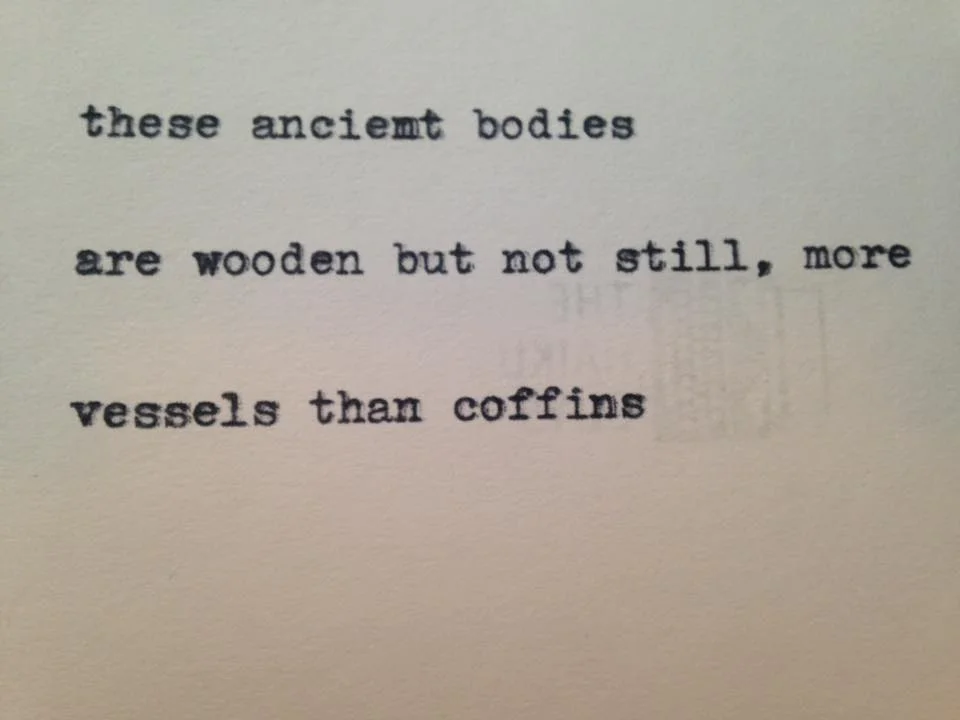

You can imagine that the audience pictured above was quite different from the typical Salastina crowd. The trimmings, too, were different. A BBQ caterer from the Crenshaw district served hotdogs and chili. An attractive young woman sold artisanal paletas in flavors like coconut and lime. And two charming, bearded hipsters -- the Haiku Guys -- sat at a table with typewriters, making conversations that culminated in personalized haikus.

My favorite of the two haikus written for me by Micah Greenberg. It lives in my violin case.

The whole thing felt more like a summer block party than a concert. We had a blast. In writing this entry, I came across a review of that night's concert, complete with pictures that brought back great memories. It illustrates the community spirit of the event:

"We’ve written before about Kensington’s concert series at the Viaduct as the best secret party in LA (and it’s true). But they actually started out much smaller—showcasing live music on the porch of their own backyard. You really can’t get any more “neighborhood” than that. What’s remarkable is how Kensington has been able to create that same incredibly intimate feeling even as their event spaces grow and expand. Whether it’s a backyard porch, a park under the bridge Downtown or a refurbished church in Highland Park, it all just feels like hanging out at your coolest friend’s house, appreciating some good tunes, good food and good people together. Creating community is what they do best."

Taking the casual context of the event into account, we decided to play mostly lighter fare.

"The opening act begins to play and we follow the beautiful chamber music melodies into the church. Salastina Music Society is on the small stage of the open hall under the gilded words “Enter His Gates with Thanksgiving”. A mix of auditory wonder and nostalgia simultaneously stirs up inside of us as the quartet performs a Star Wars suite before launching into some classical Americana to get our toes tapping."

At the end of the day, this performance felt more like community outreach than something that achieved our desired intent -- which was audience development. My guess is that social context has everything to do with that.

"Afterwards, folks spill back out into the Highland Park night with a gleam in their eyes and lightness in their step—all warmth and smiles, lit up from the inside. This is what inevitably happens at any Kensington event…you leave feeling like you just took part in something really special, something sacred that can never be recreated. You just have to be lucky enough to be there when the moment strikes and get that little piece of LA heaven, that little piece of Home."

That really says it all: FOMO is tied to a sense of belonging, and the desire for it. Our challenge as presenters of chamber music is to ignite that same feeling, despite the marketing challenges inherent to the culture around classical music.

A happy, human scale

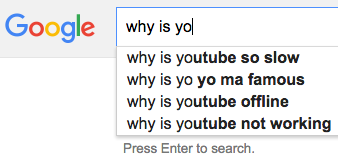

As we've seen over and over -- at Nirav's, at Kensington Presents, and at dozens of our main series performances -- chamber music connects uniquely. About a week and a half ago, I witnessed mastery of human connection through music on the largest scale. Yo-Yo Ma performed with LACO.

The man has a singularly disarming way of interacting with others. His genuine kindness and generosity of spirit comes through. He took every opportunity to let us know how great he thought we sounded. This was done in a sincere, not ingratiating, way. If anything, you got the feeling he knew how much a compliment would mean coming from him; it was true kindness that compelled him to deliver it, as if he'd be doing us all a disservice by keeping it to himself.

He also possesses an incredibly natural way of navigating the elitism of classical music. The fact that classical music represents a pinnacle of human achievement becomes an effortless, warm invitation. It's hard to describe, but it's just his way. Yes, you feel elevated by it; but you also feel, albeit humbly, like you belong with it.

Music is who he is; sharing it with others is what he does. This self-evident effortlessness -- coupled with a notable lack of pretentious evangelizing -- is magnetic.

Check out #2 below. Even the internet is puzzled by Yo-Yo Ma-gic.

Youtube: 3. Yo-Yo: 1.

As cellist Gregory Sauer put it:

"To him, music making is about connections between artist and audience, artist and composer, composer and audience ... It's so easy when one is busy and stressed about the next performance to forget that each individual in that concert hall is looking for a connection. Yo-Yo's strength is that he never loses sight of that most important fact."

After the concert, one of my Colburn students who'd attended pointed out how great it was when Yo-Yo looked into the audience while he was playing. Actually looking at who you're communicating with, rather than performing for: what a concept!

After rehearsing Haydn's cello concerto in c major.

After the house concert at Nirav's, Kevin and I engaged in our usual post-mortem. We swapped stories from the night, telling each other highlights from conversations we'd had. As tends to happen, I found myself crystallizing a thought through our conversation. I realized that sharing what's special to us about music in an intimate way -- letting people into that -- likely means more to others than even we realize.

To me, Yo-Yo Ma's way -- and the adoration it's earned him -- represents what classical music aspires to on the largest scale. What a privilege to have had so many experiences this month to remind me of why I do what I do.